διδάσκουσα: Σοφία Ντενίση

χειμερινό εξάμηνο 2018-9

σημειώσεις του Εμμανουήλ Νίνου

8ο μάθημα Τρίτη 27 Νοεμβρίου 2018

Κάρολος Ντίκενς

Όλιβερ Τουίστ

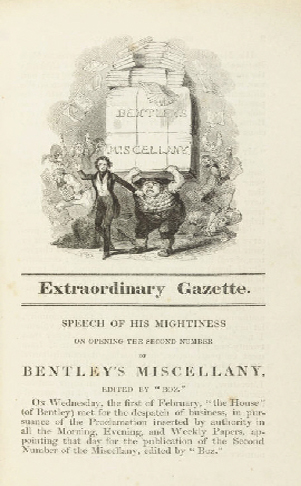

RICHARD BENTLEY NEW BURLINGTON STREET

LONDON 1838

volume 1

Bentley's Miscellany was an English literary magazine started by Richard Bentley. It was published between 1836 and 1868.

Already a successful publisher of novels, Bentley began the journal in 1836 and invited Charles Dickens to be its first editor. Dickens serialised his second novel Oliver Twist, but soon fell out with Bentley over editorial control, calling him a "Burlington Street Brigand". He quit as editor in 1839 and William Harrison Ainsworth took over. Ainsworth would also only stay in the job for three years, but bought the magazine from Bentley a decade later. In 1868 Ainsworth sold the magazine back to Bentley, who merged it with the Temple Bar Magazine.

Aside from the works of Dickens and Ainsworth other significant authors published in the magazine included: Wilkie Collins, Catharine Sedgwick, Richard Brinsley Peake, Thomas Moore, Thomas Love Peacock, William Mudford, Mrs Henry Wood, Charles Robert Forrester (sometimes under the pseudonym Hal Willis), Frances Minto Elliot, Isabella Frances Romer, The Ingoldsby Legends and some of Edgar Allan Poe's short stories. It published drawings by the caricaturist George Cruikshank, and was the first publication to publish cartoons by John Leech, who became a prominent Punch cartoonist.

Charles John Huffam Dickens

(7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870)

Oliver Twist is a 2005 drama film directed by Roman Polanski.

Un roman-feuilleton est un roman populaire dont la publication est faite par épisodes dans un journal.

serial literature

In literature, a serial is a printing format by which a single larger work, often a work of narrative fiction, is published in smaller, sequential installments.

Χριστόφορος Σαμαρτσίδης [Σαμαρτζίδης]

(Λευκάδα 1843 - Κωνσταντινούπολη 1900)

Lumpenproletariat

is a term used primarily by Marxist theorists to describe the underclass devoid of class consciousness. Coined by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in the 1840s, they used it to refer to the "unthinking" lower strata of society exploited by reactionary and counter-revolutionary forces, particularly in the context of the revolutions of 1848. They dismissed its revolutionary potential and contrasted it with the proletariat.

Among other groups criminals, vagabonds, and prostitutes are usually included in this category.

Jeremy Bentham

(/ˈbɛnθəm/; 1748 - 1832)

was an English philosopher, jurist, and social reformer regarded as the founder of modern utilitarianism.

Bentham defined as the "fundamental axiom" of his philosophy the principle that "it is the greatest happiness of the greatest number that is the measure of right and wrong". He became a leading theorist in Anglo-American philosophy of law, and a political radical whose ideas influenced the development of welfarism. He advocated for individual and economic freedoms, the separation of church and state, freedom of expression, equal rights for women, the right to divorce, and the decriminalising of homosexual acts. He called for the abolition of slavery, of the death penalty, and of physical punishment, including that of children.[9] He has also become known as an early advocate of animal rights.[ Though strongly in favour of the extension of individual legal rights, he opposed the idea of natural law and natural rights (both of which are considered "divine" or "God-given" in origin), calling them "nonsense upon stilts". Bentham was also a sharp critic of legal fictions.

The Act has been described as "the classic example of the fundamental Whig-Benthamite reforming legislation of the period".[1] Its theoretical basis was Thomas Malthus's principle that population increased faster than resources unless checked, Thomas Malthus's "iron law of wages" and Jeremy Bentham's doctrine that people did what was pleasant and would tend to claim relief rather than working.[2] The Act was intended to curb the cost of poor relief, and address abuses of the old system, prevalent in southern agricultural counties, by enabling a new system to be brought in under which relief would only be given in workhouses, and conditions in workhouses would be such as to deter any but the truly destitute from applying for relief. The Act was passed by large majorities in Parliament, with only a few Radicals (such as William Cobbett) voting against. The act was implemented, but the full rigours of the intended system were never applied in Northern industrial areas; however, the apprehension that they would be was a contributor to the social unrest of the period.

The iron law of wages is a proposed law of economics that asserts that real wages always tend, in the long run, toward the minimum wage necessary to sustain the life of the worker. The theory was first named by Ferdinand Lassalle in the mid-nineteenth century. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels attribute the doctrine to Lassalle (notably in Marx's 1875 Critique of the Gotha Programme), the idea to Thomas Malthus's An Essay on the Principle of Population, and the terminology to Goethe's "great, eternal iron laws" in Das Göttliche.[1][2][3]

It was coined in reference to the views of classical economists such as David Ricardo's Law of rent, and the competing population theory of Thomas Malthus. It held that the market price of labour would always, or almost always, tend toward the minimum required for the subsistence of the labourers, reducing as the working population increased and vice versa. Ricardo believed that happened only under particular conditions.

The Newgate novels (or Old Bailey novels) were novels published in England from the late 1820s until the 1840s that were thought to glamorise the lives of the criminals they portrayed. Most drew their inspiration from the Newgate Calendar, a biography of famous criminals published at various times during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, but usually rearranged or embellished the original tale for melodramatic effect.

Among the earliest Newgate novels were Thomas Gaspey's Richmond (1827) and History of George Godfrey (1828), Edward Bulwer-Lytton's Paul Clifford (1830) and Eugene Aram (1832), and William Harrison Ainsworth's Rookwood (1834), which featured Dick Turpin. Charles Dickens' Oliver Twist (1837) is often also considered to be a Newgate novel. The genre reached its peak with Ainsworth's Jack Sheppard published in 1839, a novel based on the life and exploits of Jack Sheppard, a thief and renowned escape artist who was hanged in 1724.

workhouse

In England and Wales, a workhouse, colloquially known as a spike, was a place where those unable to support themselves were offered accommodation and employment.

The New Poor Law of 1834 attempted to reverse the economic trend by discouraging the provision of relief to anyone who refused to enter a workhouse. Some Poor Law authorities hoped to run workhouses at a profit by utilising the free labour of their inmates, who generally lacked the skills or motivation to compete in the open market. Most were employed on tasks such as breaking stones, crushing bones to produce fertiliser, or picking oakum using a large metal nail known as a spike, perhaps the origin of the workhouse's nickname.

Life in a workhouse was intended to be harsh, to deter the able-bodied poor and to ensure that only the truly destitute would apply. But in areas such as the provision of free medical care and education for children, neither of which was available to the poor in England living outside workhouses until the early 20th century, workhouse inmates were advantaged over the general population, a dilemma that the Poor Law authorities never managed to reconcile.

χειμερινό εξάμηνο 2018-9

σημειώσεις του Εμμανουήλ Νίνου

8ο μάθημα Τρίτη 27 Νοεμβρίου 2018

Κάρολος Ντίκενς

Όλιβερ Τουίστ

RICHARD BENTLEY NEW BURLINGTON STREET

LONDON 1838

volume 1

Bentley's Miscellany was an English literary magazine started by Richard Bentley. It was published between 1836 and 1868.

Already a successful publisher of novels, Bentley began the journal in 1836 and invited Charles Dickens to be its first editor. Dickens serialised his second novel Oliver Twist, but soon fell out with Bentley over editorial control, calling him a "Burlington Street Brigand". He quit as editor in 1839 and William Harrison Ainsworth took over. Ainsworth would also only stay in the job for three years, but bought the magazine from Bentley a decade later. In 1868 Ainsworth sold the magazine back to Bentley, who merged it with the Temple Bar Magazine.

Aside from the works of Dickens and Ainsworth other significant authors published in the magazine included: Wilkie Collins, Catharine Sedgwick, Richard Brinsley Peake, Thomas Moore, Thomas Love Peacock, William Mudford, Mrs Henry Wood, Charles Robert Forrester (sometimes under the pseudonym Hal Willis), Frances Minto Elliot, Isabella Frances Romer, The Ingoldsby Legends and some of Edgar Allan Poe's short stories. It published drawings by the caricaturist George Cruikshank, and was the first publication to publish cartoons by John Leech, who became a prominent Punch cartoonist.

Charles John Huffam Dickens

(7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870)

Un roman-feuilleton est un roman populaire dont la publication est faite par épisodes dans un journal.

serial literature

In literature, a serial is a printing format by which a single larger work, often a work of narrative fiction, is published in smaller, sequential installments.

Επιφυλλιδικό μυθιστόρημα

Χριστόφορος Σαμαρτσίδης [Σαμαρτζίδης]

(Λευκάδα 1843 - Κωνσταντινούπολη 1900)

Lumpenproletariat

is a term used primarily by Marxist theorists to describe the underclass devoid of class consciousness. Coined by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in the 1840s, they used it to refer to the "unthinking" lower strata of society exploited by reactionary and counter-revolutionary forces, particularly in the context of the revolutions of 1848. They dismissed its revolutionary potential and contrasted it with the proletariat.

Among other groups criminals, vagabonds, and prostitutes are usually included in this category.

Jeremy Bentham

(/ˈbɛnθəm/; 1748 - 1832)

was an English philosopher, jurist, and social reformer regarded as the founder of modern utilitarianism.

Bentham defined as the "fundamental axiom" of his philosophy the principle that "it is the greatest happiness of the greatest number that is the measure of right and wrong". He became a leading theorist in Anglo-American philosophy of law, and a political radical whose ideas influenced the development of welfarism. He advocated for individual and economic freedoms, the separation of church and state, freedom of expression, equal rights for women, the right to divorce, and the decriminalising of homosexual acts. He called for the abolition of slavery, of the death penalty, and of physical punishment, including that of children.[9] He has also become known as an early advocate of animal rights.[ Though strongly in favour of the extension of individual legal rights, he opposed the idea of natural law and natural rights (both of which are considered "divine" or "God-given" in origin), calling them "nonsense upon stilts". Bentham was also a sharp critic of legal fictions.

Poor Law Amendment Act 1834

The Act was passed two years after the 1832 Reform Act extended the franchise to the middle classes. Some historians have argued that this was a major factor in the PLAA being passed.The Act has been described as "the classic example of the fundamental Whig-Benthamite reforming legislation of the period".[1] Its theoretical basis was Thomas Malthus's principle that population increased faster than resources unless checked, Thomas Malthus's "iron law of wages" and Jeremy Bentham's doctrine that people did what was pleasant and would tend to claim relief rather than working.[2] The Act was intended to curb the cost of poor relief, and address abuses of the old system, prevalent in southern agricultural counties, by enabling a new system to be brought in under which relief would only be given in workhouses, and conditions in workhouses would be such as to deter any but the truly destitute from applying for relief. The Act was passed by large majorities in Parliament, with only a few Radicals (such as William Cobbett) voting against. The act was implemented, but the full rigours of the intended system were never applied in Northern industrial areas; however, the apprehension that they would be was a contributor to the social unrest of the period.

The iron law of wages is a proposed law of economics that asserts that real wages always tend, in the long run, toward the minimum wage necessary to sustain the life of the worker. The theory was first named by Ferdinand Lassalle in the mid-nineteenth century. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels attribute the doctrine to Lassalle (notably in Marx's 1875 Critique of the Gotha Programme), the idea to Thomas Malthus's An Essay on the Principle of Population, and the terminology to Goethe's "great, eternal iron laws" in Das Göttliche.[1][2][3]

It was coined in reference to the views of classical economists such as David Ricardo's Law of rent, and the competing population theory of Thomas Malthus. It held that the market price of labour would always, or almost always, tend toward the minimum required for the subsistence of the labourers, reducing as the working population increased and vice versa. Ricardo believed that happened only under particular conditions.

The Newgate novels (or Old Bailey novels) were novels published in England from the late 1820s until the 1840s that were thought to glamorise the lives of the criminals they portrayed. Most drew their inspiration from the Newgate Calendar, a biography of famous criminals published at various times during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, but usually rearranged or embellished the original tale for melodramatic effect.

Among the earliest Newgate novels were Thomas Gaspey's Richmond (1827) and History of George Godfrey (1828), Edward Bulwer-Lytton's Paul Clifford (1830) and Eugene Aram (1832), and William Harrison Ainsworth's Rookwood (1834), which featured Dick Turpin. Charles Dickens' Oliver Twist (1837) is often also considered to be a Newgate novel. The genre reached its peak with Ainsworth's Jack Sheppard published in 1839, a novel based on the life and exploits of Jack Sheppard, a thief and renowned escape artist who was hanged in 1724.

workhouse

In England and Wales, a workhouse, colloquially known as a spike, was a place where those unable to support themselves were offered accommodation and employment.

The New Poor Law of 1834 attempted to reverse the economic trend by discouraging the provision of relief to anyone who refused to enter a workhouse. Some Poor Law authorities hoped to run workhouses at a profit by utilising the free labour of their inmates, who generally lacked the skills or motivation to compete in the open market. Most were employed on tasks such as breaking stones, crushing bones to produce fertiliser, or picking oakum using a large metal nail known as a spike, perhaps the origin of the workhouse's nickname.

Life in a workhouse was intended to be harsh, to deter the able-bodied poor and to ensure that only the truly destitute would apply. But in areas such as the provision of free medical care and education for children, neither of which was available to the poor in England living outside workhouses until the early 20th century, workhouse inmates were advantaged over the general population, a dilemma that the Poor Law authorities never managed to reconcile.

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου